‘Fast & Furious’ Technical Advisor Craig Lieberman Remembers the Great Car Film

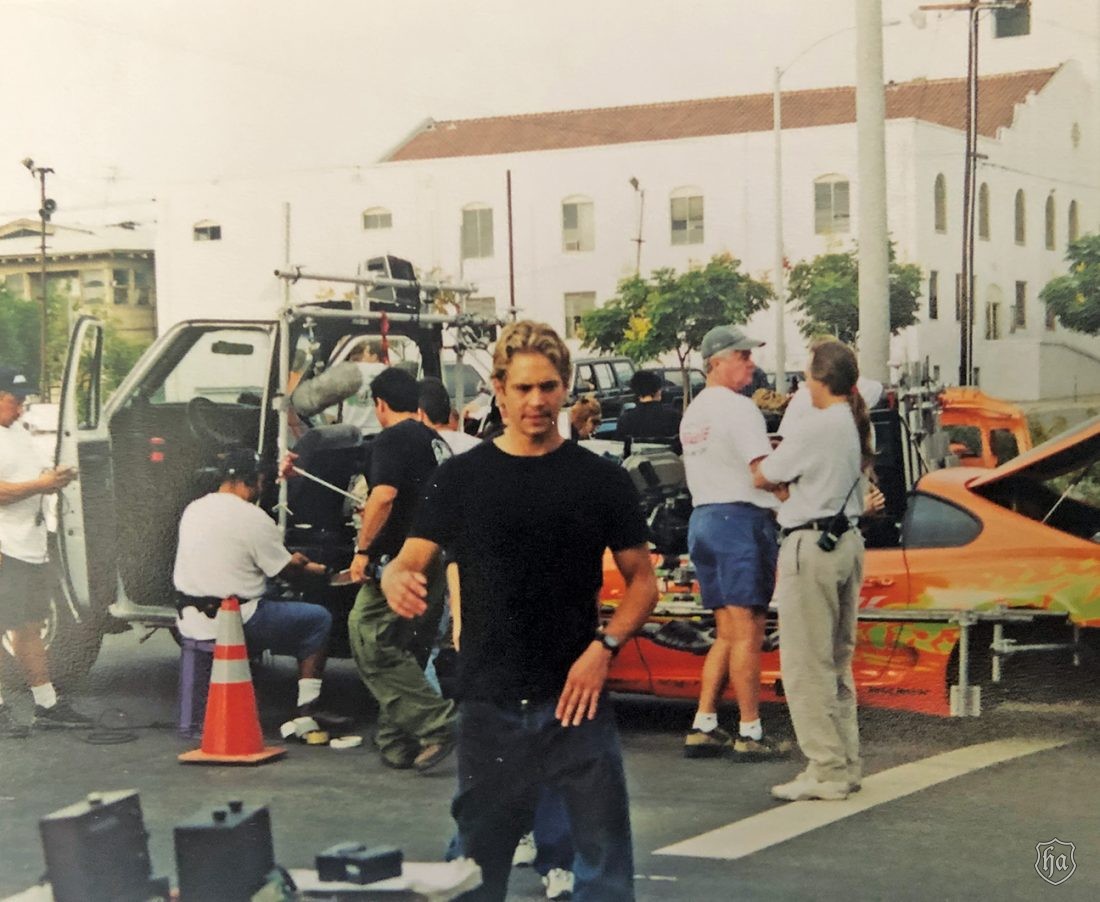

Craig Lieberman deserves a lot of credit for the “Fast & Furious” movies. Look for him lower on the end credits, though, than the late Paul Walker, the vibrant young star of the popular car flicks, which represented a hard shift in American car culture more than 20 years ago.

Technical advisor on the first two (of ten) “Fast & Furious” movies by Universal Pictures, Lieberman starred big time, with a significant role in curating and compiling the tuner cars featured in those films. These “tuner” cars have components and modifications to make them faster.

Beginning with the first film in 2001, the series centered on street racing and its culture of bolt-on parts and death defiance: nitrous injection, turbos and dual turbos, superchargers and high-output manifolds. They pioneered enthusiast films celebrating fast-to-the-point-of-furious imports which had been souped up and tricked out not by the manufacturers but by young performance-driven enthusiasts.

The franchise also includes short films, a television series, toys, video games, live shows and theme park attractions. Universal produced and distributed all of the films.

These weren’t American muscle cars that defined the ’50s and ’60s: hot Corvettes with chrome sidepipes, Ford Cobras with racing-level small and big blocks, Ram Air Pontiac GTOs and Hemi Cudas. Instead, the car stars were Toyotas, Hondas, Mitsubishis, BMWs and Mazdas; these replaced the bigger, weightier gas-hungry street burners following the fuel crisis and engine detuning of the 1970s.

“At first nobody believed that these were for real. After all, Japanese sports cars were just economy cars introduced to America following World War II,” Lieberman recalls. “Back in the day, parents wanted their kids to drive economical cars with good mileage — but the kids were out at night at the street races.”

He adds: “All of a sudden, in the 1990s, we started seeing these crazy car shows, like “Hot Import Nights,” and dedicated import strip drag races.” In his mid-50s today, Lieberman was too old to hop in and joy ride with those new devotees. At the time, the California native was working with automotive marketing companies.

Some of his contemporaries back then, raised on the car pop hits of Jan and Dean and the Beach Boys, were asking him if this new ethos was a fad, transformative or transitory. Was this the swan song of the predatory muscle cars seeking their next street race victim?

“You would go to the tuner events and find thousands of people buying these cars for $12,000 and putting another $30,000 in parts for them,” he recalls. “It was insane. People were buying these things they didn’t even need, that they couldn’t afford to impress people they didn’t know. It was crazy.”

Backlot Car Casting

Although his dad was not a car guy, Lieberman has been a fan since youth, raised on Hot Rod magazine, the original Adam West Batmobile and “Speed Racer” cartoons and car shows featuring monster big block V-8s and skimpily covered women who quickly transformed Beaver Cleavers into men, car dreamers into car doers. “When I get my car, I said to myself it will have buttons and gadgets just like that,” Lieberman remembers.

Around the turn of the century, he was showing his yellow 1994 twin-turbo Toyota Supra at a car show in Manhattan, California; a middle-aged man wearing a Hawaiian short and sandals admired it. He was David Martyr, a producer; his wife Kool also worked at Universal Studios. The men exchanged contacts.

Martyr called Lieberman, then with car-focused Peterson Publications, and visited his office, which featured a glossy of that super Supra proudly hanging on a wall. Martyr told him that he was a consultant on a movie called “Red Line” and asked him to “come down and see the folks at Universal.”

Lieberman was asked to the director’s office at the studio. And he kept asking himself, “Why am I here? Why am I here?” But the staff liked him and what he could offer. He would help pick the cars, tweak the script and educate them about the tuner car culture, what’s good, what’s bad.

Pressed, he suggested the top tuner cars within a few minutes: the highly respected but expensive Nissan Skyline GTR (R33 or an R34 if one could be acquired); Acura NSX; Honda S2000; Mitsubishi 3000GT; Nissan 300zx; Mazda Rx7 (FD body style); and a Toyota Supra mk IV or mk III. “I wanted to make sure that if this movie was going to be made about tuner cars, that we had all of the best ones in it, the ones that people had been worshiping since the launch of the Gran Turismo game in 1997,” he says.

Money was an immediate issue. In 2000, Universal’s new chief, Ron Lynch, told the production team that there would only be a $25-million budget. Reading the script, Lieberman estimated that the film would need at least 40 cars “to do it right.” So, at the starting line, the film was short millions.

Exacerbating this, the studio had responded to the first dailies, or footage produced each day, with “ho-hums” for a film high revving as “Red Line.” Yawning, they declined on more money.

Martyr and crew, with Lieberman’s input, cut another reel; the producers liked it. “They were really fired up, and we got our money.” But the budget for the cars was just still only $2 million, including buying them, renting them, modifying them and fixing them. The final cost was $39 million; the film today would need $125-million today, he says.

To “do it right,” Lieberman suggested, four or five copies of each car would be needed, but that would be impossible if they were all new. Lynch suggested that to save money the main or “Hero” cars be rented from private owners. “This would be the first time a motion picture didn’t build cars from scratch,” he says.

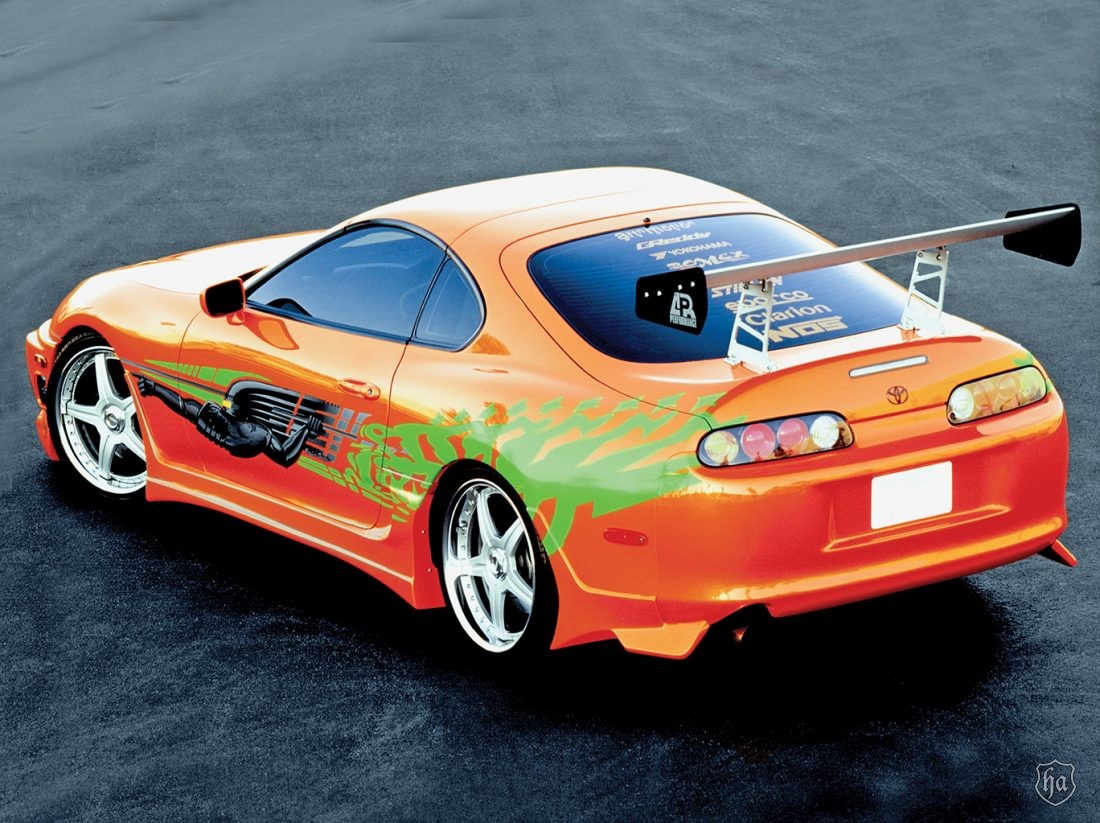

The star car, “Hero 1,” is usually the shiniest, prettiest, most pristine car, the one you see Walker or costar Vin Diesel driving. “Hero 2” would be a cosmetic replica of Hero 1; it would lack components such as a working audio system but would have the turbos and other power upgrades for the racing and chase scenes.

“We would use dark tinted windows to hide the fact corners were cut on the interior of these cars to save money,” he explains. When the car is moving, no one would notice that the two cars were not the same.

In addition, two other versions would be required. “Stunt 1” would be a “beater” they’d buy off the internet. “Stunt 2” was in the same used condition as Stunt 1, a “backup for the backup.”

For these, the studio used local mechanics and technicians to create cosmetic replicas of the hero car. “They painted them, slapped on some decals, a body kit, and everything else was just spray painted, glued on covered up or even Xeroxed such as gauges attached to the A pillars,” Lieberman says. “They went crazy putting all of the equipment in the cars.”

The crew scheduled a number of casting calls on the lot, with Lieberman the director. All of the cars were sourced in the Los Angeles area. If it could only be found in Japan, they’d simply not have the time or the money to import it.”

All the cars had to be stock at a fair market price. The highest paid for a nonHero car was $24,000, and most were under $18,000; one was $9,900, another $11,000. All would sell today for $70,000 or more, he says.

Secondly, they had to be easy to replicate with bolt-on parts and no custom fab work. “We were looking for cars that could be replicated without too much difficulty,” he explains. “Again, we didn’t have the time or the budget.”

So cars with blended widebody kits, headlight or twilight swaps or any car with any crazy custom fabrication work or cars with elaborate interiors including multiple television sets were eliminated. And, if someone’s car wasn’t at one of the lot appraisals, the team would not select it if they couldn’t see it.

A chosen car also had to have strong aftermarket support, with a good selection of parts. “These are cars people would put a poster up on their walls of and dream about owning that car one day,” he says.

Finally, it needed to have an automatic transmission for the stunt drivers because stunt drivers don’t like driving manual cars. “This complicates the stunts; they don’t want to focus on shifting, when steering and sliding,” Lieberman explains.

Led by Lieberman, the team also developed a “just-in-case” backup list, including an Acura Integra; BMW e36 M3; Honda Civic or Del Sol; Mazda Miata; Nissan 240sx (s13/14); Toyota Celica, MR2 (sw20 mk II) or AE86; and a Subaru Impreza.

The Finish Line

When Universal first approached Lieberman, the team didn’t know what cars would work for what roles in the film. At first, Paul (Brian in the film) would have a Mitsubishi 3000GT and then an Eclipse. But when Lieberman showed them his six-speed manual ’94 Mk IV Supra, the team recessed to discuss.

After a series of reviews and more lot casting calls, Craig then compiled a recommended list of cars for of the characters.

Because Walker was the star, he would drive Lieberman’s six-speed twin turbo Supra. For Hero 2, the group bought an automatic-trans Supra for about $22,000 and quickly reupholstered the interior. For about another $8,000, the shops made fake gauges and added other aftermarket bits.

Vin, who played Dom, got a ’93 Mazda RX7, which had to have the roll cage removed because of the actor’s size. He also received the beautiful ’69 Dodge Charger R/T built by Cinema Vehicle Services, with a replacement engine, which was returned after filming; the supercharger was fake, braced for the moment to the engine.

Mia drives a ’95 Acura Integra sourced from June Shih; Jesse a ’96 VW Jetta from Scott Centra; Vince, Lieberman’s ’99 Nissan Maxima SE; Leon, a ’95 R33 GT-R from Sean Morris at Motorex; Letty, a ’95 Nissan 240sx from Helen Cho; Johnny Tran, a ’99 Honda S2000 from RJ DeVera; HICE, ’93-’95 Civics bought through Auto Trader and the internet; Edwin, a ’96 Acura Integra GSR sourced from Bill Kohl; and Hector, a 94’ Civic Si sourced from Nick Stewart.

Lieberman remained at the studio for the second film, “2 Fast 2 Furious” and moved on to an international car-consulting career he continues today. After colorfully telling the new director for that third film a Dodge Neon wouldn’t make it as the Hero car of the third film, “I called my wife on the way home and told her, ‘I think I’ve been fired.’”